Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

What I learned playing "SteamProphet"

75% of indie games make almost nothing. What else can you learn by playing "fantasy football" with indie games on Steam?

Yesterday I tweeted a thread with some scary stats (click through to see the whole thing):

I'm going to tread carefully about this thread:https://t.co/HqlJ5XyO0d

— Lars Doucet (@larsiusprime) May 8, 2017

A quick updated summary of some of the things I noted:

At least 249 indie games have launched on Steam in the past 13 weeks

not including VR or F2P games

that's more than 30 games every week, on average

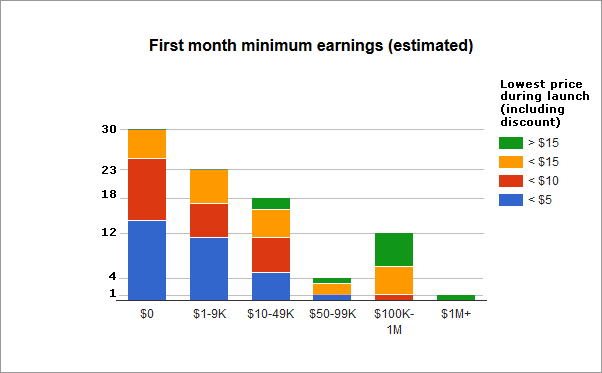

In their first month...

75% made at least $0

10% made at least $1K-9K

7.5% made at least $10K-49K

2% made at least $50K-99K

5% made at least $100K-999K

Exactly one made > $1M

Here's a graph:

What you're looking at is minimum estimated earnings for each game, in their first month on Steam. If a game is pegged at "$0" that doesn't mean it made $0, it just means I don't have enough data to confidently state it made any more than that. (Doing some spot checks with willing developers, it seems that games in the $0 tier make a few thousand in their first month at best).

How did I get this data, you ask?

Let's Play SteamProphet

For the past thirteen weeks I've been playing a little game with a small group of friends I like to call "SteamProphet," and it's basically fantasy football for indie games on Steam.

(UPDATE: we have a website now.)

Every Sunday, I put together a list of upcoming games releasing on Steam in the next week, with a few filters (must be tagged "indie", no VR, no F2P, must have a concrete release date, etc). Each player selects a "portfolio" of five games from the list they think will do well, and selects one game as their top weekly pick.

Four weeks later we score the results and see who did best. We calculate a pessimistic minimum estimate for how much money each game has earned, and a player's score for that week is the sum of each game's individual score, plus the score for their weekly pick (the weekly pick is the same game as one of the five regular picks).

Scoring

In the first iteration we simply used the lower bound of SteamSpy's "players" metric for each game to count as the score. We prefer the "players" metric over "owners" because it's less susceptible to distortions from giveaways, bundles, free weekends, and metric-inflation scams.

"Owners" counts anyone who has the game in their Steam library, whether that's a paying customer, a journalist who got a free review copy, or a smurf account trading greenlight votes for game keys. The "players" metric represents someone who actually bothered to install and run the game, and although this figure is still gameable, it's harder to do. Most importantly, we're pretty sure that "Players" will correlate closer to actual purchasers than "Owners", especially in a game's first month. To be extra conservative, we take the lower bound, so for a figure like "Players total: 58,263 ± 6,959" we count that as 51,304 players. Since SteamSpy uses a statistical confidence interval of 98%, taking the lower bound means we can be 98% confident the actual number of players is at least that high.

However, just counting players makes it hard to compare differently priced games -- $2.99 easily garners more players than $19.99. To normalize scores, we multiply players by the lowest price in the game's first month, rounded down to the nearest 1,000. This makes it easier to compare the relative success of two different games.

But since we're dealing with estimates rather than hard figures from developers themselves, we insist on being conservative. This scoring method stacks four ruthless forms of pessimism:

Use players instead of owners (players is always < owners)

Use the lower bound

Use the lowest price

Round down

What we're left with is a pretty reliable "hit detector." If a game scores 100,000 points with this estimation method, we can be pretty sure that it's actually earned at least $100,000 on Steam. The only major fly in the ointment is regional pricing -- if everyone who bought the game was from Russia or China, then the actual purchase price could be significantly lower, but as long as western buyers represent a significant chunk (a near certainty), the built-in pessimism should more than account for this.

If we wanted to create a "miss detector" instead, we would probably do the opposite -- go with the most optimistic estimate possible in each case; take the upper bound of the owners metric and multiply by the highest price, and count that as a pretty confident ceiling on a game's earnings (on Steam, at least) -- and a low ceiling could reliably indicate a flop. But that wasn't our chief concern -- we wanted to know which games had almost certainly done well.

Predicting

The predicting part of the game was inspired by the concept of "Superforecasters" -- a group of people who try to actually get better at predicting future events (a much-needed skill in our age of non-stop punditry). The basic gist of their method is:

Make clear, quantifiable, falsifiable predictions.

Bad: The economy will do better.

Good: The S&P 500 will close higher than 3000 points.

Set a maturation date for the prediction.

Bad: The economy will do better "soon"

Good: The S&P 500 will close higher than 3000 points on January 1, 2018

Keep score.

Go back and see if your predictions came true.

If not, try to figure out why you were wrong.

After a game's already launched it's really easy to say, "Oh yeah, obviously Super Sandwich Quest did poorly on Steam -- it's clearly not what Steam's audience wants." But do you have the confidence to say that in advance? How many games have you been super hyped for that actually did well? Are you sure you really know "what Steam's audience wants?"

Here's a quick example -- which game did you think would do better, Night in the Woods, or Northgard?

They both released the same week. Night In The Woods was a super-hyped, long-awaited indie title that, judging by my twitter feed, all the "cool kids" were talking about. Northgard was some sort of Viking RTS / village sim about to launch into Early Access, by an obscure developer most of you probably hadn't heard of. If I hadn't been a personal acquaintance of the developer, I would have missed its launch entirely.

Night in the Woods did great -- it scored 653 thousand SteamProphet points, but Northgard positively blew it out of the water with 1.259 million points.

Nobody in our group called it.

Heck, even I underestimated it, and I'd been following Northgard's development since the start because I'm a big personal fan of the game's creator, Nicolas Cannasse (he created the Haxe programming language I use every day). Sure, it's easy to look back now and say -- "well, clearly, games like Banished have done well, Northgard is actually pretty innovative, and its production quality far exceeds the typical game entering Early Access, so of course it was a massive hit."

But before it launched, all I could think was -- "sure, it looks cool, but, don't we have enough Viking games already? Is it really what Steam's audience wants? Do people play this kind of game?"

Apparently so. Since we started SteamProphet 13 weeks ago, Northgard still holds the title of #1 best performing game.

And it's an early access game!

Shows what I know.

Hindsight

As it turns out, the most valuable lesson I learned from playing SteamProphet wasn't the predicting part. I mean, I did learn that I totally suck at predictions (despite having invented the game, I routinely score in the bottom half of my group), and that's a valuable lesson in itself.

But the much more important reward is the fine-tuned sense of presentation you start to develop by looking at every single indie game that releases on Steam and scrutinizing their pitches, screenshots, titles, and -- most importantly -- trailers. It's a brutally humbling experience.

One key lesson is how important it is to make a good trailer. So many indies frankly have awful trailers, and it's the number one thing that somebody's going to judge your game on. What makes a good trailer? Here's the secret -- I don't even need to tell you.

ATTENTION: This is important!!!!

Just go to this list of upcoming indie games on Steam. Click on each one. Watch the trailer. Do that for the next 15 minutes. When you're done, I guarantee you will come away with a better sense of what makes a good and bad trailer than when you started. And I bet you'll be a lot more careful when it comes time to make the trailer for your next game.

Making and shipping a game is hard. It takes a long time. Hundreds of hours. Often thousands. Whether you're a grizzled veteran or a first-timer, This One Weird TrickTM will save you loads of grief:

Once a week, spend 15 minutes watching trailers for upcoming indie games.

Not only will you get a better sense for how to present (and not present) your game, but you'll also get a very sobering reminder of exactly how crowded this space is, and how important it is to make sure you stand out.

That's seriously the most important thing I learned from this whole thing. The rest is fine-tuning. That said, here's some other interesting things I learned from SteamProphet:

Case Studies

Thimbleweed Park released the same week as Rain World and Beat Cop. Despite being a huge Ron Gilbert fan and mega-hyped for the game, my heart sank when I saw the main trailer posted on its Steam page:

Now, Ransome is a funny character, and the production quality of this trailer is good, but -- were they really leading with this? People who had no idea what this game was about were about to come away with the impression, "Pixelated point and click adventure game featuring a weird obnoxious clown who curses a lot," rather than, "Highly anticipated classic-style adventure game by Monkey Island creator Ron Gilbert, featuring a large cast of colorful characters, with a distinct 90's Twin Peaks / X-Files sorta vibe."

So, I picked Rain World over Thimbleweed for my top pick.

Luckily, they updated the trailer right before launch, putting their best foot forward:

Thimbleweed went on to score 674,000 SteamProphet points, beating Rain World and Beat Cop handily.

As for Rain World, it looked gorgeous, was all over my twitter feed, and had an awesome trailer when it came time to make my prediction. It did pretty good -- 147,000 points -- but not as well as I had predicted. This might be post-hoc rationalization, but I think Rain World struggled because many players came in expecting an awe-inspiring exploration game in a dangerous world, but instead found something more like a precision platformer mixed with a punishing survival sim.

Again, this just means that we are fairly sure Rain World made at least $147,000. It probably earned more, but we can't say how much. It also launched on Playstation 4, and we have no idea what it earned there.

Another surprise I had was Shovel Knight: Specter of Torment. It scored only 5,000 SteamProphet points, and pretty much everyone had it pegged for their top pick of the week. This one's a little harder to explain -- maybe it did better on consoles? Maybe new customers opted to buy Shovel Knight: Treasure Trove instead, which includes Specter of Torment? In any case, my intuition failed me once again.

A case where I was dead right, however, was Little Nightmares. Several other players were skeptical of how it would do on Steam, but I stuck to my guns. Its final score isn't even due until next week and it's already up to 8,873,000* 777,000 SteamProphet points. Yes, that's over 8 million*, 700 thousand and it's a lower bound. Seems kind of weird to classify a game published by Bandai-Namco as "indie" but that's a discussion for another day :P

*Don't fat-finger the calculator, kids.

But my biggest embarassment of all is not calling Yooka-Laylee. Not only did I pass it over for the top pick, I didn't even pick it as one of my five basics! Why would I do something like this? Well, the pre-release buzz about the game was pretty negative and I was sure we had another Mighty Number 9 on our hands. Turns out I was living in a bubble and a lot of people really enjoyed the game. Its score hasn't matured as of this writing, but it's already up to 2,051,000 points. Granted, it was kickstarted so some of those are probably kickstarter keys, but -- they're actually playing the game, so that's a sign of real engagement. We're still iterating the rules of SteamProphet and there's some ongoing debate for how to settle edge cases like these.

Now, there's one final thing I want to talk about before we circle back to the beginning.

Low Price is No Man's Land

Jeff Vogel once famously explained How You're Going To Price Your Computer Game:

Flip a coin. If it's heads, $15. If tails, $20. Done!

The data strongly supports this position:

What you're looking at here is a chart of indie games in each earnings tier, color-coded by the lowest price they had during launch. As you can see, games priced below $5 and $10 are strongly clustered at the bottom. Games priced at > $15 did significantly better -- not a single one made less than $10K, and most of them made at least $100K. Games priced between $10 and $15 were spread out across the scale. Only one game had an earnings floor above $1M, and it was priced at $20.

Notably -- exactly one game was priced lower than $10 and still managed an earnings floor of $100K. That game was Hidden Folks, which is an abnormally appealing game for that price point:

It's important to draw the right conclusions from this data. For one, it's not the biggest sample size ever (especially for the $1M+ tier). More importantly, it's a classic mix of correlation/causation -- I'm pretty sure raising the price on some random game isn't going to make it perform better. What's more likely happening is that games naturally fit into certain perceived "production quality" tiers that developers (and players) use to peg their prices.

That said, if you've put in the effort to meet a certain perceived quality bar, don't price your game for pennies. For whatever reason, Steam Players seem pretty strongly anchored around the $10, $15, and $20 tiers, so it might be dangerous to slip outside that range and naively count on an Econ 101 price elasticity slope. I'm pretty sure Hidden Folks could have safely pegged themselves at $9.99 without shedding too many customers, but good for them in any case!

Sober Up

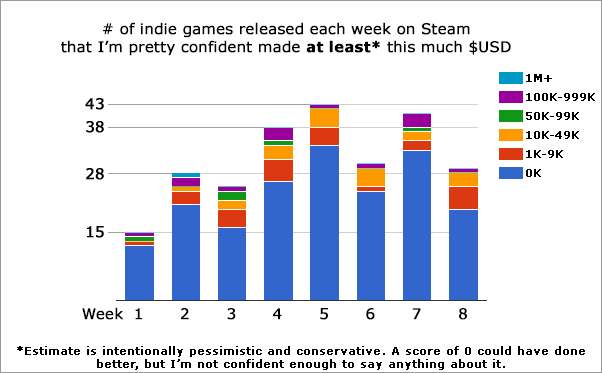

Now, let's circle back to that scary little graph at the beginning:

Each week, dozens of indie games release on Steam, and the vast majority of them will make very little money. And if you don't get that initial boost of traction, Steam's discovery algorithms are unlikely to lift you out.

The /r/gamedev thread I linked earlier features a lot of developers concerned about this. Many of them understandably express frustration with visibility rounds; these were changed recently from giving each developer a free 500,000 impressions on the Steam front page, to only targeting existing customers and those who have wishlisted your game about recent updates. As I detailed in my article Steam Discovery 2.0, Stegosaurus Tail 2.0, this was a huge boon for established developers like me, but a lot of first-time developers feel cheated.

I think Valve should rename "Visibility Rounds" ASAP -- the name is seriously misleading and the broken expectations are not good for the community.

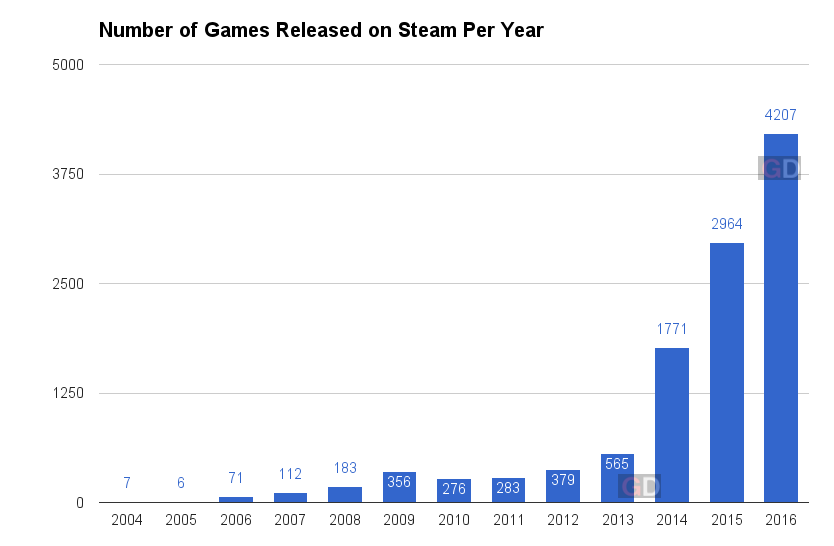

That said, I don't think it's possible to change visibility rounds back to the way they used to be, and simple math can attest to why:

chart source: game-debate.com

In 2016 alone 4,207 games were released on Steam. If every single one of those games was given 500,000 free impressions, that's 2,103,500,000 (over two billion) impressions. And that's just if each game spends one visibility round. In the old system games got as many as five of these. If each game in 2016 spent all five visibility rounds, now we're talking about ten billion impressions.

But hey! There's a lot of Steam users to spread that out over, right? Steam's concurrent users bobbles around the 7.5-14 million range. Taking the extreme high end, let's say 14,000,000 are online at any given time and also assume super generously that all of them logged into the steam storefront at all times, ready to spread out impressions, rather than just skipping the storefront to play CSGO and DOTA2 (which is what most of them are actually doing). Even then, it's still over 150 impressions per concurrent user, for one visibility round per game, for just the games released in 2016. At this rate, the old style of visibility rounds would completely overtake the Steam storefront with indie game impressions. It was a system that could only work in an uncrowded system.

The hard truth is just that there's more indie games on Steam than ever before. Steam's discovery system doesn't actively bury new games as much as being buried is the natural default state in such a crowded environment. And for first time indies, any measure to hard-cull the store front could just as easily exclude their own games. Sure, there were some obvious cynical shovel-ware titles, but the majority of what I saw were earnest efforts by first-timers, even if many were rough around the edges (just like my games were when I first started out).

The silver lining is that if you pay close attention, you can get a pretty good sense of what the climate on Steam is like, and what you can do to improve your chances. I've been making games professionally for almost a decade now, and I've seen lots of developers come and go in that time. I'm still here (for now).

If you want to stay afloat in a storm, it's really important to know which way the wind is blowing.

Everything is hard, good luck out there.

Update:

Okay, after getting like a billion requests to join my SteamProphet league, and people asking how to set up their own, I put together a little site with all that information:

If you want to join one of my leagues, or just want more information when it's available, put your contact details in this form:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfSso9yzaazVmRBfXFuYFNuMcIGgWJyBpQqwPnCJ7X1jrHMgg/viewform?usp=sf_link

Thanks!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like