Sponsored By

News

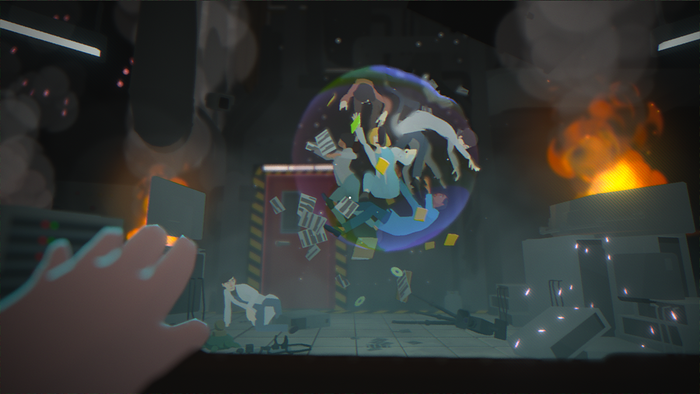

Jesse Faden in Remedy Entertainment's Control.

Business

Remedy adds Control director Mikael Kasurinen to central management groupRemedy adds Control director Mikael Kasurinen to central management group

Working with Alan Wake 2's Sami Järvi, Kasurinen will help guide Remedy's future and ensure the Control and Alan Wake games meet the studio's goals.

Daily news, dev blogs, and stories from Game Developer straight to your inbox