Sponsored By

News

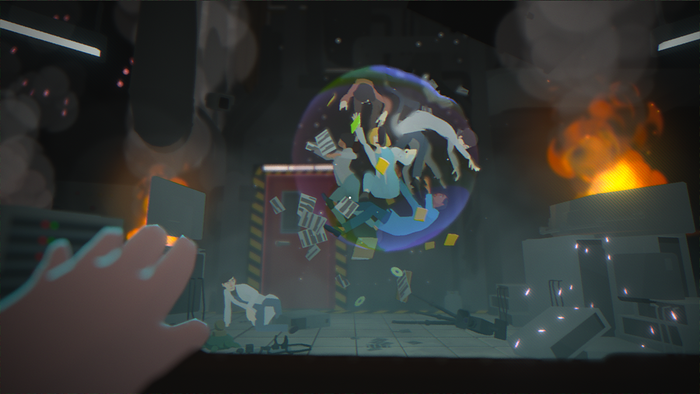

Key art for 2024's Another Crab's Treasure.

Business

Another Crab's Treasure sells 30,000 units within its first dayAnother Crab's Treasure sells 30,000 units within its first day

Aggro Crab's third game is yet another 2024 indie doing pretty well right out the gate.

Daily news, dev blogs, and stories from Game Developer straight to your inbox