Sponsored By

News

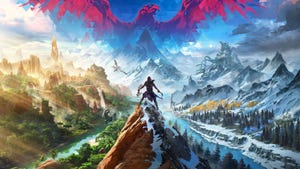

Teaser image for Rebel Wolves' debut project, Dawnwalker.

Business

Rebel Wolves' Konrad Tomaszkiewicz wants to avoid repeating his CDPR pastRebel Wolves' Konrad Tomaszkiewicz wants to avoid repeating his CDPR past

Tomaszkiewicz opens up on his dreams for his new studio and how he's using it to address prior allegations of bullying at CD Projekt Red.

Daily news, dev blogs, and stories from Game Developer straight to your inbox