Sponsored By

News

The Thunderful logo on a black background

Business

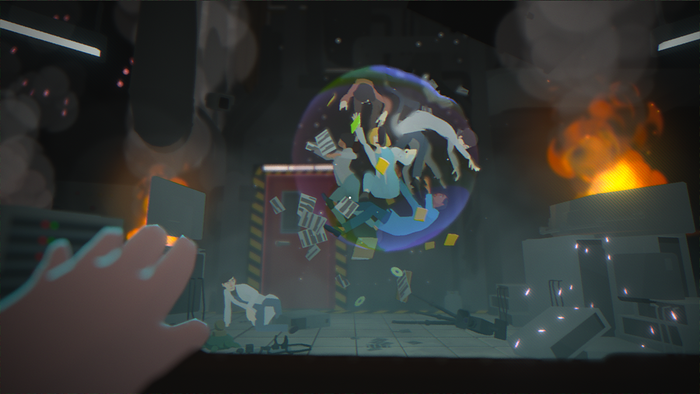

Struggling publisher Thunderful divesting Nordic Game SupplyStruggling publisher Thunderful divesting Nordic Game Supply

The Swedish conglomerate laid off 20 percent of its workforce in January and has now started offloading "non-strategic assets."

Daily news, dev blogs, and stories from Game Developer straight to your inbox