Sponsored By

thumbnail

Design

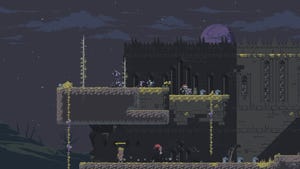

Making the berry sweet return to Celeste on its sixth anniversaryMaking the berry sweet return to Celeste on its sixth anniversary

Art director Pedro Medeiros de Almeida tells us how a one-week game jam brought the beloved title from 2D to 3D, resulting in Celeste 64.

Daily news, dev blogs, and stories from Game Developer straight to your inbox